A Battle for Reconciliation Looms in 2026

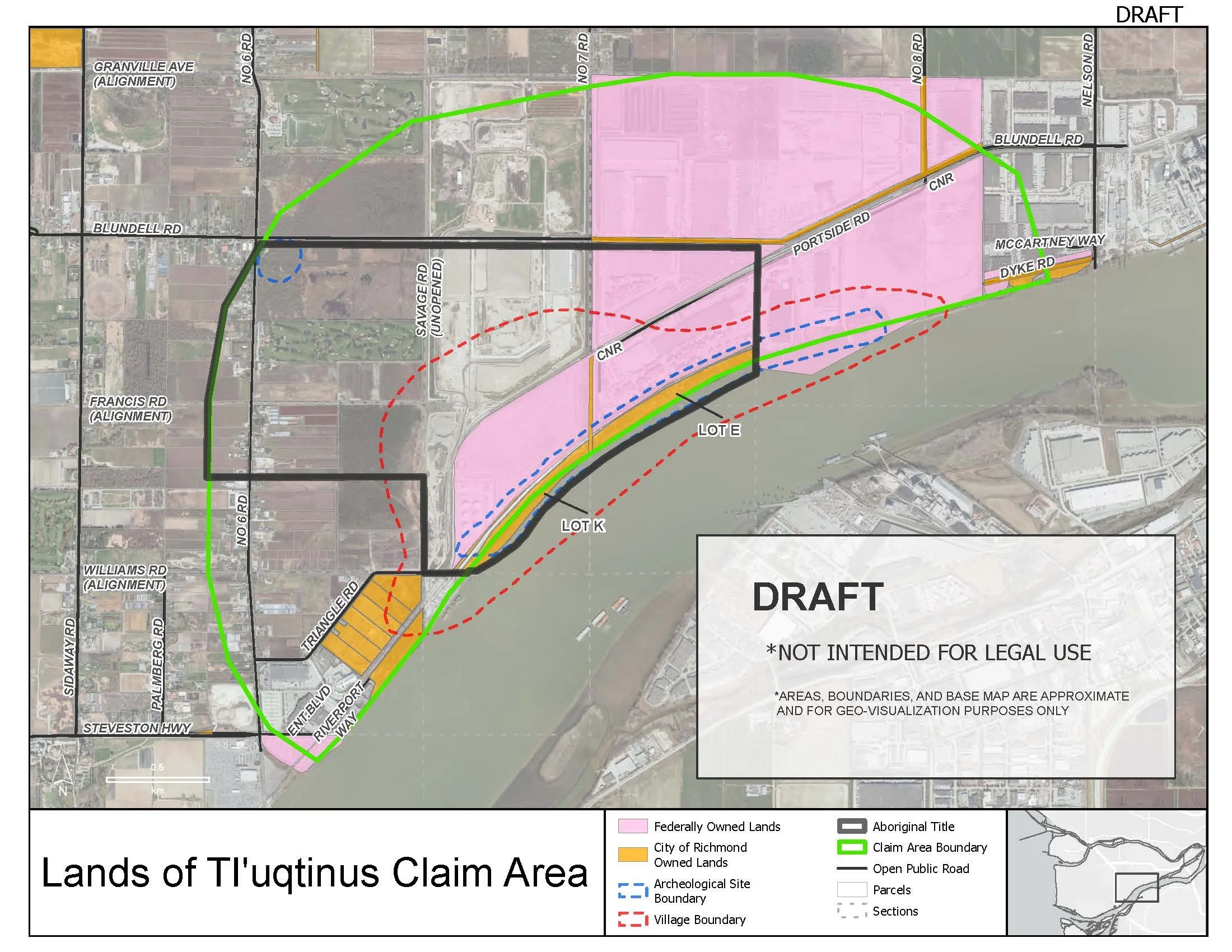

The lands in south Richmond, B.C., claimed by the Cowichan peoples in their 2014 case to seek recognition of their jurisdiction over lands owned by various companies. From a notice circulated by the mayor of Richmond, found at https://www.richmond.ca/__shared/assets/mapclaimarea77880.pdf

As we look ahead to a new year, I want to draw our attention to a landmark case working its way through Canada’s justice system. The eventual decision in the case of Cowichan Tribes v Canada will bring us to new frontier in the process of reconciliation.

When residential school survivors began Canada’s current process of reconciliation two decades ago, it brought to light a longer process of reconciliation that our courts had been struggling with for years – reconciling our commitment to the rule of law with Canada’s current economic, social and political realities.

In the case of Delgamuukw v. British Columbia decided in 1997, for example, the Supreme Court wrestled with the reality that Aboriginal people owned territory in Canada prior to the arrival of Europeans. What does that mean for property rights in Canada today?

In England, the traditional basis for property rights is an assumption that at some point the King must have owned all land, and granted or sold portions to his subjects. But no European monarch knew nothing about this land until 1497, let alone owned any of it.

Because Canada was never conquered, and because no British or French monarch ever claimed to have acquired territories in our country by conquest, Canadian law required a different basis for property rights. How did the Crown acquire the land? Well, by law of course. If Canada is nothing else, it is a country that honours the rule of law.

This also matches the historical record. The vast majority of territory in this land, from coast to coast to coast, came under control of Europeans through a sale, treaty or other legal transaction. If the courts of today are to protect the property rights of those who now own land, it follows that they must acknowledge that the parties that sold or traded the land to the Crown had a legal basis to it.

This is the origin of the principle of Aboriginal title. Property rights in Canada and inextricably bound up with the principle that land has been the subject of law for centuries and centuries. Take away Aboriginal title, and you take away private property in Canada. It is a cornerstone of the rule of law in Canada.

Aboriginal title was confirmed in our Constitution in 1982, and subsequent Court decisions have confirmed that it grants First Nations claims to territory in certain cases, above and beyond any claim that the Crown might have. These cases include rural lands in areas such as 1750 square kilometres near Williams Lake, BC, where the Tsilhqot'in Nation won recognition of its exclusive rights in a 2014 decision.

The courts have not ruled, so far, in any case involving land titles held by individual Canadian landowners. That is likely because of the political power of landowners, and the political and economic disruption that a protest on their part might occasion if they disagree with a court decision. It was fears of this kind led the Supreme Court to water down Aboriginal rights in other cases such as the Delgamuukw decision.

Which brings us to the case of Cowichan Tribes v Canada. A riverside stretch of Richmond in the southern stretches of greater Vancouver was historically a village called Tl’uqtinus where people of the Stz’uminus, Penelakut and Halalt First Nations lived for many generations. Collectively, these peoples are known as the “Cowichan tribes,” because of their shared connection to a dialect called “Quw’utsun Mustimuhw.”

In 1853 the British Governor of Vancouver Island, James Douglas, negotiated an agreement with the Cowichan tribes to offer the Crown’s protection in their lands in return for peace with the newly-arriving settlers. The lands were later sold to various industrial interests to run a port in the same location, but in 2014, the same Cowichan peoples asserted their claim to some 758 hectares of this land.

It took 11 years, amid the vast mobilization of non-Indigenous parties to contest the case, but in August 2025 the BC Supreme Court ruled that about 300 hectares of the lands claimed could not be considered “fee-simple” since the rights to the land cannot possibly come from the Crown but instead from the prior Aboriginal title.

Note that there are no individual landowners affected by this decisions. Indeed, the Cowichan plaintiffs have loudly and repeatedly declared their support for the property rights of the landowners. The only parties impacted directly by the decision are industrial landowners.

But note, even more importantly, that land ownership remains sacrosanct, it is only the jurisdiction under which the ownership exists that shifts - back to the original authorities that had the rights all along and which Governor Douglas had acknowledged so long ago.

The real significance of this case is that the Supreme Court established that this case sets a precedent for all property in Canada. The reconciliation of Canada’s ancient history with the current realities has therefore taken a step ahead.

But 2026 will prove to be a crucial year for defending this step. Because already the non-Indigenous political opponents of reconciliation are mobilizing.

In a December 28 article in the Atlantic, Republican commentator David Frum denounced the Cowichan decision, issuing a call to arms to all propertied Canadians to organize a political movement to force governments not to honour the court’s decision. He admits that the court’s decision doesn’t invalidate any property rights, but argues that confusion about which jurisdiction applies might depress market prices. Justice be damned, he argues, we can’t allow market uncertainty to reduce the value of our assets.

It’s a familiar pattern, powerful non-Indigenous interests seeking to undermine the rule of law because of worries about the impact on their wealth. He even throws in some residential-school denialism and some gratuitous references to Indigenous substance abuse to clarify his ideological alignment.

So as 2026 dawns we are seeing the battle lines for reconciliation drawn. On the one hand, courts upholding the rule of law based on historical realities, implementing what genuine equality of rights between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians. And on the other, denialists infuriated about threats to the relative value of their the wealth they have accumulated under institutionalized inequality.

David Frum even attributes the return of the rule of law in this land to the harmless land acknowledgements that rule-of-law minded Canadians recite. Surely Indigenous people themselves can’t be the agents of change in Canada; it must be us woolly-minded democracy-loving Canadians. It’s fatuous to presume that we are driving this change, but if the opponents of reconciliation think land acknowledgements have an impact, we should continue issuing them.

So as the battle looms in this New Year, fellow Remembering Project volunteers, let us say our land acknowledgements loudly and proudly. The Canada we have dreamed about, of First Nations, Métis and Inuit nations living in equality and dignity alongside us, is coming into focus, if we can muster the strength to ensure the rule of law stands in the land we share.

Ben Rowswell